1. Introduction

With the rapid development of China’s economy, China is doubling down on technological innovation as a primary driver of growth in the pursuit of high-quality development. By building digital villages, the country is improving its public services, tilting more favorable policies and market information toward rural areas. As early as 2005, the No. 1 Central Document began to pay attention to agricultural informatization and rural informatization. In 2010, Opinions on Promoting the Construction of Optical Fiber Broadband Networks, jointly issued by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the National Development and Reform Commission and seven other ministries and commissions, made it clear that it was imperative to accelerate the construction of rural information infrastructure by using optical fiber broadband, so to improve the capacity of information infrastructure in rural areas.

New technologies are vital economic drivers and have advanced economic development in China’s rural areas. In order to comply with this trend, the No.1 Central Document of 2018 for the first time explicitly proposed “the digital village strategy” which aims to accelerate the penetration of the digital economy into rural areas. The Outline of the Digital Village Development Strategy released in 2019 provides a road map for digital village development in China, while the Digital Village Development Guideline 1.0 released in 2021 provides comprehensive and authoritative suggestions for both provincial and country levels to promote the application of digital technology in various economic and social sectors in China’s rural areas. Subsequently, important documents in China for consecutive years have continuously requested various localities to promote the construction of digital villages and integrate them with real on-site conditions.

Digital village construction, an important step in realizing rural revitalization, successfully addresses the “three rural” (sannong) issues, which concern agricultural, farmer and rural communities, through extensive digital initiatives. According to the China Digital Village Development Report, more than 3.95 million new jobs were created by the end of June 2020. Rural residents are better equipped with knowledge and skills that are required of digital workers, achieving a steady increase in the level of disposable income, and a continuous narrowing of the income disparity between urban and rural areas.

However, data from the Statistical Yearbook released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics shows that, the income disparity between the high- and low-income groups in rural areas continues to widen, with the absolute value of the income gap at 38,225.6 RMB in 2022, doubled that of 2013. The widening of the income gap between different groups within rural areas has a significant impact on all aspects of rural life, in particular on the relative hardship and limited future development capacity of low-income rural population. Meanwhile, the income disparity between rural areas in different regions of China, and the extent of the income disparity between rural residents in different regions exceed the extent of the overall gap in regional development. This has to do with the sequence of development in different rural areas, with those that develop first having more opportunities and potential for capital, wealth accumulation, and capacity building, making the gap wider.

The construction of digital villages is aimed at promoting the solution of the problem of unbalanced and insufficient development through digital means, continuously narrowing the gap between regions, urban and rural areas, groups and basic public services, and promoting the sharing of the dividends of development in the digital age by rural residents, so as to help realize common prosperity in high-quality development. Therefore, it is of great practical value to scientifically evaluate and analyze the characteristics of the current situation of the digital village construction, determine the development disparities of different regions and reveal its impact on China’s rural income disparity.

In view of this, we use a fixed-effect model based on China’s provincial panel data to explore the impact of digital village construction on rural income disparity, to provide explanations and countermeasures for the realistic existence of income disparity. The results of this study will effectively assist rural areas in making strategic choices to grasp the new opportunities of the new round of scientific and technological revolution and industrial change, and git the goal of promoting common prosperity in high-quality development in rural China.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on the Rural Income Disparity

Existing literature has paid more attention to the urban-rural income disparity and the income disparity among urban residents, while there are fewer studies on the income disparity within China’s rural residents.

In this literature, there are relatively more discussions on the methods of measuring the internal income disparity of rural residents and more commonly used measurement indicators, such as Gini coefficient, Thayer index, coefficient of variation, extreme difference, extreme difference rate, and relative change index of per capita net income of rural population. The Gini coefficient is a common indicator used internationally to measure the income disparity between residents of a country or region, with values ranging from 0 to 1. The lower the value, the more evenly the wealth is distributed among the members of society, and vice versa. 0.4 is usually taken as the “warning line” of the income distribution gap. Based on the above considerations, we use the Gini coefficient in the benchmark regression to calculate the rural income disparity.

Some other studies revolve around the influencing factors of the rural income gap, such as the unbalanced development of the non-agricultural industry, differences in agricultural labor productivity, and the equity of education in rural areas. In the process of economic growth, the unbalanced development of the non-agricultural industry will bring about a shock effect on the residents’ incomes and income structure, which will exacerbate the widening of the rural income gap [

1]. Based on panel data from 2000 to 2014 in China, domestic scholars have conducted many studies on the factors affecting the rural income disparity, such as labor productivity, the investment in education funding, the improvement of education equity. They believe that agricultural labor productivity has different effects on the income disparity within rural residents in different thresholds and the improvement of education in rural areas of China can only serve to reduce the income disparity within rural areas [

2,

3].

2.2. Research on the Digital Village Construction

Agricultural and rural informatization has laid a solid foundation for the construction of digital villages, which is both an urgent task and a key measure for building a modern countryside [

4]. Regarding the construction of digital countryside, most of the existing studies are qualitative in nature, and domestic scholars have discussed the logic of digital countryside strategy development [

5], and the connotation of digital village construction. Digital village construction has an important role in promoting urban-rural integration and rural industrial structure optimization [

6], eliminating the urban-rural digital gaps and promoting the implementation of rural revitalization strategy [

7]. But under the guidance of the triple objectives of overall coordinated development, regional collaborative revitalization and urban-rural integration of digital village construction, China’s digital village construction has achieved milestones [

8].

However, there are problems such as large funding gap and shortage of local talents [

9], lagging construction of rural digital infrastructure and lack of technical support [

10], and the focus of work falls on hardware and equipment and digital formalism breeds and spreads [

11], and propose innovative industrial development mode to store into industrial prosperity and multiple collaborative governance to promote rural [

12], improve the institutional mechanism of digital village construction and enhance the quality of rural information infrastructure supply [

13], and other implementation paths. On the basis of clarifying the theories related to digital countryside, digital village construction promotes high-quality agricultural development by tapping the potential advantages of developing agriculture, strengthening agricultural science and technology innovation, and transforming traditional production factors [

14]. Zhu and Chen constructed an evaluation index system for the development of China’s digital countryside from four major aspects: funding, industry, infrastructure, and services, and explored the temporal evolution, regional differences, and spatial distribution of digital village construction in 30 provinces in China, finding that the level of digital countryside development is in a development trend of gradual improvement, with large regional disparities [

15].

At the same time, some literature also affirms that the use of digital technology in the process of digital village construction has promoted rural residents’ income [

16,

17]. In addition, some scholars have discussed the path of building digital villages in western China [

18] and ethnic regions in China [

19], and its impact on rural consumption, food system resilience, industrial prosperity, mismatch of agricultural resource factors, county ecological environment, and rural residents’ income increase [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] were further studied and some important recommendations were made, which provide useful references for this and future studies.

2.3. Research Gaps Analysis

The above literature provides insights for the research of this paper, but no relevant literature has been found that directly explores the impact of digital village construction on rural income disparity. In view of this, we conduct an empirical study based on provincial panel data from 2011 to 2020 and take digital village construction as an entry point to explore the impact of digital village construction on rural income disparity and its mechanism of action.

The marginal contributions compared to the existing studies are: first, there are few studies examine the impact of the important strategy of digital village construction on rural income disparity in China. Second, among the exsting studies on digital village construction, there is little literature analyzing the measurement of the level of digital village development and the trend of spatial and temporal evolution. Therefore, we construct an evaluation index system for the level of digital village construction based on documents such as the Outline of Digital Village Development Strategy, the Digital Village Construction Guideline 1.0 and the Digital Village Construction Guideline 2.0, starting from the aspects of rural infrastructure, agricultural development and the life of rural population, to enrich the quantitative research on the construction of digital village.

3. Context

The digital village construction based on data and technology will promote industrial prosperity through resource optimization, structural upgrading and common sharing, inject new momentum for high-quality agricultural development, and provide thrust for further achieving the goal of common prosperity on the basis of rural revitalization strategy. We provide an in-depth analysis of the mechanism of the role of digital village construction on the income disparity within rural areas in China.

3.1. Influence of Digital Village Construction

Digital village construction helps improve the construction of rural digital information infrastructure and promote agricultural land transfer and development of rural industries, which increases both agricultural income and non-agricultural income.

In terms of agricultural income, in the context of the key policy of the comprehensive demonstration counties for e-commerce in rural areas, the digital village construction has facilitated the rapid development of e-commerce across the country by improving the construction of information infrastructure significantly reducing various costs in agricultural product transactions, and greatly facilitating the transfer of agricultural land. When both large-scale farmers and small farmers participate in the transfer of agricultural land, the profitability of agricultural production increases. Moreover, low-income households with limited financial resources turn to smallholder production, relying mainly on their own labor for intensive agricultural production, lower production costs, and higher marginal productivity of land. As a result, low-income households with a small income base that turn to expanding agricultural production are likely to experience higher increases in net income from agricultural production than high-income households.

In terms of non-agricultural income, digital village construction can drive rural residents’ non-agricultural employment by expanding the channels of their information sources and educational resources, improving rural residents’ cognitive level, improving the level and quality of the rural labor force, and lowering the employment threshold of non-agricultural industries to a certain extent, thus increasing non-agricultural income. On the other hand, digital village construction reduces the transaction costs of land transfer, and more production factors such as labor are reconfigured from agriculture to non-agriculture, thus increasing non-agricultural income.

Digital village construction contributes to upgrading agricultural industry. As it continues to advance, the digital village construction based on 5G, technology activates the productivity of various elements by integrating scattered land, talents and other resources in rural areas, promotes the integration and development of farming, agricultural and sideline product processing and rural transportation and logistics, broadens the industrial chain, drives the emergence of new industries and new forms of business, optimizes the structure of rural industries and provides a large number of diversified employment opportunities for the rural labor force, which greatly broadens the income sources of rural residents, and at the same time, strengthens the probability of upward mobility of the low-income strata, thus narrowing the income disparity of residents of the rural areas.

Digital village construction empowers rural governance. More data in the village, fewer errands for rural residents. In the continuous advancement of digital village construction, the level of rural governance has been improved by creating a series of digital application scenarios that are closer to the actual needs of rural residents, such as smart village affairs, and by focusing on solving problems, challenges and obstacles in rural governance. By providing accurate services and information to rural households and investing in high-quality resources in education, healthcare, and agricultural technology, digital application scenarios are gradually increasing, and rural residents can purchase goods and have them delivered to their homes through apps such as Taobao and Meituan Select. This has greatly improved rural residents’ sense of well-being and digital literacy. In addition, through innovative education models and the implementation of high-quality farmer training, a large number of rural residents have learned various technologies and knowledge, greatly improving the income level and digital skills of rural residents with low literacy levels, and the initially forming of a new team of professional farmers adapted to the development of modern agriculture. The advancement of the digital village construction process has contributed to the modernization of rural governance and the enrichment of low-income rural residents, making their income-generating effects higher than that of higher-income rural residents, thus narrowing the income disparity in rural areas.

3.2. Targeting the Income Disparity

The development of digital countryside is an effective way to narrow the gap between urban and rural areas, the regional gap and the income gap within rural areas. Jiashan County, located in Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province, relying on the constructions of digital villages, innovatively established intelligent supervision application, a modern agricultural product quality and safety supervision system, to trace the production, processing, and marketing process. The county’s 2200 agricultural subjects are included in the supervision platform and 297 agricultural subjects are included in the traceability platform of agricultural product certificate. With the development of cooperatives economy, digital village construction has driven per capita income increase of more than 2000 yuan in 2023 in Jiashan County, giving priority to the employment of low-income farmers, narrowing the gap between the incomes of residents within the rural areas. It is expected that by 2025, the coverage rate of low-income rural residents will reach more than 80%, the average annual growth rate of disposable income per capita of low-income rural residents will be more than 10%, and the disposable income per capita will reach 32,000 RMB.

Xingwen County in Sichuan Province is located at the border of four provinces. In the past, constrained by location conditions and inconvenient transportation, it held on to large tracts of land and forest land, but remained poor. The per capita net income level of rural residents in the county was at a very low level, with large internal income gaps and particularly serious income inequality. Over the past decade, in the process of promoting the construction of digital villages, Xingwen County has promoted the digital transformation of rural industries, rural communication, rural governance and rural decision-making through the construction of rural digital infrastructure. The standard of living of rural residents has improved dramatically, and the construction of the digital village has contributed to this. 1.32 billion RMB of rural e-commerce transactions were realized in 2020. More than 30 e-commerce trainings have been conducted, involving more than 900 people. The rate of agricultural and sideline product production enterprises entering the network is as high as 100%, and the coverage rate of farmers’ professional cooperatives entering the network is 80%. In 2022, the per capita disposable income of the county’s rural residents reached 20,238.5 RMB, with a growth rate of 6.7% year-on-year.

Both of the above cases demonstrate that rural areas in different regions have utilized digital village construction to develop rural economy, raise the incomes of rural residents, especially the incomes of low-income groups, and successfully realize the reduction of the intra-rural income gap. However, though the case studies can provide a detailed description of the process of digital village construction and help researchers to grasp the nature of the impact of digital village construction on the rural income gap, their low reliability and validity affect the persuasiveness of the research to a certain extent.

Reducing the income gap in rural areas is the key to alleviating poverty and realizing the common prosperity of rural residents. At present, the income of rural residents has been increasing, but the phenomenon of rural income disparity has always existed due to the differentiation of farm households and the uneven development of rural areas. Therefore, in this study, we adopt a quantitative method to conduct an empirical study on the mechanism of digital village construction affecting the income gap in rural areas. Taking a macro perspective, we use the data from 20 provinces (cities and districts) in China, and apply different measures to measure the rural income gap to further ensure the reliability of the research conclusions.

4. Methods and Measurements

4.1. Empirical Model

In order to explore the impact of digital village construction level on rural income disparity, we take the Gini coefficient (

GINIi,t) as the explanatory variable in the benchmark regression, and the digital village construction level (

DIG_Vi,t)as the core explanatory variable, and establishes the panel model shown in equation (1):

In equation (1),

GINIi,t represents the Gini coefficient of province

i in year

t;

DIG_Vi,t represents the digital village construction level;

controli,t is the five control variables affecting the rural income disparity, and

γ is the coefficient of the corresponding control variables;

µi represents the unobserved individual fixed effects;

εi,t is the random disturbance term.

4.2. Variables and Measurements

We are interested in understanding how digital village construction influences the rural income disparity. Data from the China Statistical Yearbook, the China Household Survey Yearbook, and provincial statistical yearbooks of 20 provinces (municipalities and districts) from 2011 to 2020 are used for analysis.

Provinces of Heilongjiang, Tianjin, Hunan, Yunnan, Jilin, Shandong, Hainan, Tibet, Qinghai, and Ningxia, etc., were not included in the analysis due to the lack of necessary data in the statistical yearbooks.

4.2.1. Measures of Income Disparity

Rural income disparity can reflect the income differences between different groups in rural areas and also the distribution of rural income. The Gini coefficient is an indicator of the fairness of income distribution, defined by American economist Albert Hirschman in 1943 based on the Lorenz curve. The Gini coefficient is between 0 and 1, and 0.4 is usually taken as the “warning line” of income distribution disparity, which is an authoritative indicator used internationally to comprehensively examine the income distribution disparity within the population. Based on the above considerations, we adopt the Gini coefficient (

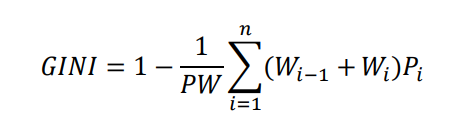

GINIi,t) to measure the income disparity within the rural areas, and its calculation formula is shown in Equation (2):

where, GINI is the Gini coefficient,

µ is the expected value of the total income of each equal subgroup,

N is the number of groups, and

yi indicates the income of individual

i.

Due to changes in the statistical caliber in China, there are differences in the way rural residents’ income is grouped in the statistical yearbooks of each province in China, some provinces are divided into low, medium-low, medium, medium-high- and high-income levels according to the quintiles of the surveyed population, while some provinces are divided according to different income intervals. Therefore, in order to ensure the consistency of the calculation caliber, this paper adopts the calculation formula in the text of Tian Weimin to measure the Gini coefficient of rural residents [26], which is shown in Equation (3):

where,

P is the total population,

W is the total income,

n is the number of subgroups, and

Wi is the income accumulated to the

ith group, and accordingly,

Pi is the population accumulated to the ith group.

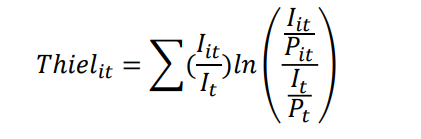

In addition, in order to ensure the reliability of the research findings, we conduct a robustness test by calculating the Thiel index, which is used as an alternative to the Gini coefficient. The Thiel index is calculated by Thiel on the basis of the concept of “entropy” in information theory for income distribution, and the larger the index, the more obvious the income gap. Thiel index is mainly used for robustness testing, and its calculation formula is shown in Equation (4):

where

t is the year,

Ii,t and $$\frac{I_{it}}{P_{it}}$$ are the rural income and rural disposable income per capita in the ith region, respectively,

It denotes the total income of each region in year

t, and

Pi denotes the total population of each region in year

t.

In order to visualize the evolution of the spatio-temporal pattern of China’s rural income disparity, we use the natural breakpoint grading method in ArcGIS software to intermittently grade the rural Gini coefficient of 20 provinces in the country in 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020, respectively, and divide it into high, medium, and low grades according to its relative development, and the results of its spatial visualization are shown in –.

From 2011 to 2014, the overall spatial distribution of the Gini coefficient was relatively stable, with the overall narrowing of the rural income disparity, with Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region remaining unchanged in the first echelon (high level), and Shanxi, Jiangsu, Gansu and Zhejiang provinces, which were formerly in the first echelon (high level), falling to the second echelon (medium level), suggesting a narrowing of the rural income disparity between rural residents and a closing of the “generation gap” between rural residents, while in the third echelon (low level), only Shanghai remained stable, indicating that the region maintained a low level of income disparity from 2011 to 2014. In 2017, the Gini coefficient showed an “inverted triangle” stratification in spatial distribution. inverted triangle” stratification pattern, i.e., the number of provinces (cities and districts) with medium and high levels is high, while the number of provinces (cities and districts) with low levels is low. Specifically, the number of provinces in the first echelon has increased from 2 to 6 in 2014, with the addition of Gansu, Shaanxi, Sichuan and Guizhou provinces; the number of provinces in the second echelon has decreased, from fourteen to twelve in 2014. By 2020, the rural income disparity of the provinces originally belonging to the second echelon continues to shrink and transforms into the third echelon, leading to a rise in the third echelon of provinces from 2 to 6 in 2017, with the new addition of Shanxi Province, Zhejiang Province, Chongqing Municipality, and Beijing Municipality, which suggests that from 2014 to 2020, the number of medium- and low-level provinces gradually increases while the number of high-level areas decreases. The income disparity between residents in internal areas has been reduced, which has a contributing effect on further realizing the goal of common prosperity.

Figure 1. Spatial distribution pattern of Gini coefficient in 20 provinces of China in 2011.

Figure 2. Spatial distribution pattern of Gini coefficient in 20 provinces of China in 2014.

Figure 3. Spatial distribution pattern of Gini coefficient in 20 provinces of China in 2017.

Figure 4. Spatial distribution pattern of Gini coefficient in 20 provinces of China in 2020.

In addition, it can be seen that the medium and low-level areas are mainly concentrated in the Yangtze River Delta region, while the high-level areas are distributed in the northwestern provinces, such as the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, which are restricted by geography and natural conditions. Therefore, in the process of promoting the construction of digital villages to narrow the income disparity within the rural areas, attention should be paid to cultivating the development of the aggregation of the provinces to increase the clustering effect and thus form the radiation effect, and at the same time, the development of the currently backward northwestern regions should be emphasized as well. development of the currently backward northwest region.

4.2.2. Measures of Control Variables

Digital Village Construction Guide 1.0 proposes a general reference architecture for digital village construction, which specifically includes information infrastructure, public support platform, digital application scenarios, construction operation management and guarantee system construction. Regarding measuring the level of digital village construction, this study is guided by the documents Outline of Digital Village Development Strategy, Digital Village Construction Guide 1.0 and Digital Village Construction Guide 2.0, and refers to the index system constructed by Zhu and Chen, and considers the accessibility of data to establish evaluation from three dimensions: digitalization of rural infrastructure, digitalization of agricultural development and digitalization of rural residents’ life indicator system, and uses the entropy value method to assign weighted scores to each indicator to measure the level of digital village construction at the provincial level (see Table 1).

As shown in Figure 5, the national average level of digital village construction has increased from 0.102 in 2011 to 0.306 in 2020, indicating that the overall level of digital village construction in China shows a development trend of gradual improvement. However, the development level of each region is uneven and there are large differences. Guangdong, Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces are at the top of the digital village construction level, all higher than the national average and much higher than Qinghai, Ningxia, Hainan and Tibet, which may be related to the degree of economic, political, cultural and social development of each region (see Figure 6).

To control for the influence of other factors, we further control for the following variables: (1) industrial structure (

IS), represented by the ratio of total value added of secondary and tertiary industries to regional GDP; (2) degree of economic development (

LNGDP), measured in the form of logarithm of GDP of each province; (3) level of agricultural modernization (

LNAMI), expressed as the ratio of the total power of agricultural machinery per unit area to the total cultivated area, and taken as a logarithm; (4) the degree of government intervention (

GOV), expressed as the share of financial expenditures on agriculture, forestry and water in the regional GDP.

Table 1. Evaluation Index System of Digital Village Construction Level.

Figure 5. National average development trend of digital village construction.

Figure 6. The average level of digital village construction in 20 provinces nationwide.

4.2.3. Data Description

The descriptive statistics of each variable are shown in Table 2. The results show that the outcome variable Gini coefficient (

GINIi,t) has a mean value of 2.633, a maximum value of 0.518, and a minimum value of 0.108, and the mean value of digital village construction level is 0.222, a maximum value of 0.741, and a minimum value of 0.052, and the control variables also show the same trend, and the interval variations of the core variables are all large. It can be seen that there are large differences in the income disparity within the rural areas and the level of digital village construction in different regions.

Table 2. Variable Definition and Descriptive Statistics.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Benchmark Regression

The Hausman test was conducted and the

p-value of the difference between the regression coefficients of fixed effects and random effects was found to be significant at the 1% level to reject the original hypothesis. Therefore, the fixed-effect model is chosen to estimate Equation (4).

In order to avoid the case of pseudo-regression, we also conduct unit root test before conducting empirical analysis, and the results show that the

p-value is 0.000, which significantly rejects the original hypothesis at the 1% level, indicating that the data are effectively smooth and enhances the robustness of the regression results.

Table 3 reports the benchmark regression results. Model (1) shows that the estimated coefficient of digital village construction level is negative, indicating that digital village construction will narrow the rural income disparity, but its narrowing effect is not significant. Models (2) and (3) indicate that it is important to control for exogenous factors that may be related to rural income disparity, and shows that the effect of digital village construction in narrowing the rural income disparity is significant and increases in the magnitude.

There are also differences in the effects of control variables on the rural income disparity. Industrial structure is significantly positive at the 10% level, indicating that upgrading the industrial structure further widens the rural income disparity, which may be due to the industry’s greater demand for high-quality labor. However, the literacy level of many rural laborers is generally low, with the largest proportion having primary and junior high school literacy. Therefore, farmer stratification has emerged, widening the income disparity among rural residents. The level of economic development and the level of agricultural modernization are significantly positive at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively, indicating that higher the level of economic development and the level of agricultural modernization, the wider the rural income gap. The estimated coefficient of government intervention is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that the digital village construction has a significant correlation on reducing the rural income disparity, which may be due to the positive impact of China’s poverty alleviation policy and rural revitalization strategy on rural construction, and the increased expenditure on livelihood and social security in rural areas, which stimulates endogenous impetus for the development of rural areas.

Table 3. Impact of Digital Village Construction on Rural Income Disparity.

We also examine the role digital village construction in subsamples to ask whether our results are sensitive for different samples. Given this motivation and the availability of data, we divide our samples into three regions: Western, Eastern and Central China, and regress Equation (4) for each region to verify the role of digital village construction on rural income disparity in subsamples.

Table 4 shows that the impact of digital village construction on the rural income disparity varies across regions, and there is still a significant information deficit and “digital divide” between regions. The level of digital village construction in the eastern region is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that the increase in the level of digital village construction has significantly reduced the rural income gap. One possible reason is that the eastern region has obvious advantages in its own development, with a concentration of advantages in geographical location, economic level, market environment, infrastructure, opening to the outside world, and human resources, etc., and develops significantly faster than the central and western regions. As a result, rural residents are generally better educated and more capable of accepting and grasping new things. This raises the income level of rural residents in the eastern region, thus making the effect of digital village construction on narrowing the income disparity in rural areas even more pronounced.

For the central and western regions, the coefficients of digital village construction level are negative, but none of them passes the significance test, indicating that the role of digital village construction in narrowing the income disparity of rural residents in the central and western regions is relatively weak. The reason may be that rural areas in the central and western regions are lagging behind in economic development, the population is aging seriously, the infrastructure is not sound, and there are fewer scenes for technological application, coupled with the fact that the current use of digital content by rural residents is mainly based on basic applications such as instant messaging and online entertainment, and that their education level is generally low, and it takes some time to accept new ideas and apply new technologies, making it difficult to promote the application of complex skills and cognitive concepts required by advanced digital technologies. Therefore, the impact of digital village construction on narrowing the income disparity within rural areas is not obvious.

Table 4. Heterogeneity Analysis Results.

In order to test the accuracy and reliability of the estimation, we adopt the methods of replacing the outcome variable, excluding some samples and replacing the regression model, respectively. First, in order to measure the status of rural income disparity more comprehensively, we calculate the Theil Index, and regress it on the digital village construction level. Next, considering the impact of the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 on China’s economic and social development, the sample of the year 2020 is excluded. Considering the time trend, a two-way fixed-effect model is applied. The corresponding estimation results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Robustness test results.

Columns (1), (2) and (3) of Table 5 show the regression results of replacing the Gini coefficient with the Rural Theil Index, and it can be seen that the estimated coefficient of the level of digital village construction, is significantly negative at the 1% level, which suggests that the role of digital village construction in narrowing the income disparity in the rural areas is significant. Columns (4), (5) and (6) show the estimation results after excluding the sample of the year 2020, and it can be seen that the estimated coefficients and significance levels of the level of digital village construction are basically the same as those of the benchmark regression, and they are significantly positive at the 5% level, which suggests that the digital village construction can significantly reduce the income disparity of the rural residents. Columns (7), (8), and (9) show the regression results using a two-way fixed-effect model. The estimated coefficients and significance levels of digital village construction level are consistent with the benchmark results.

The results of the above robustness tests all indicate that the result that digital village construction can significantly reduce the rural income disparity is robust and reliable.

6. Conclusions and Discussions

6.1. Conclusions

On the basis of logical sorting of digital village construction and income disparity, we empirically analyze the impact of digital village construction on rural income disparity based on a fixed-effect model with provincial panel data from 2011 to 2020, and obtain three main research findings.

First, the overall level of digital village construction in China shows a gradual development trend, but the development level among regions is unbalanced and varies greatly, showing an unbalanced development pattern of “high in the east and low in the west”.

Second, digital village construction can significantly reduce the income disparity in the rural areas. The main reason is that, as the construction of digital village continues to advance, the information infrastructure in rural areas has been gradually improved, facilitating the transfer of agricultural land, increasing both the agricultural and non-agricultural income of rural low-income residents, and improving digital literacy and skills, which is conducive to easing the income disparity among rural residents.

Third, from a regional perspective, the digital village construction can significantly reduce the rural income disparity in the eastern region, while the digital village construction in the central and western regions does not have a significant effect. The reason may be that the eastern region has obvious advantages in its own development, and the rural residents are generally more capable of accepting and mastering new things, while the economic development of rural areas in the central and western regions is lagging, and the efficiency of rural residents in applying new technologies to increase income is relatively low.

6.2. Discussions

Digital construction plays an irreplaceable role in promoting rural development and rural revitalization in China. In the process of building digital villages, the government has made huge financial investments to achieve wide rural network coverage, precise agricultural production, informatization of agricultural markets, and more orderly rural governance. However, more attention is needed to the unbalanced development of different regions. In particular, it is necessary to cultivate the construction of digital information infrastructure and technology application in rural areas in the central and western regions, and to cultivate digital talents and promote them to play their proper roles in rural areas in the central and western regions. Meanwhile, governments at all levels should form a mechanism to guide all kinds of talents to flow to the countryside and actively participate in rural project construction, support and guide talents to serve rural revitalization. There is also an urgent need for rural residents in the central and western regions to receive further education and training in relevant skills, and to learn to focus on cultivating Internet thinking and the ability to apply information, so as to adapt to the high demands placed on the workforce by the rapid development of the economy and to raise their income levels.

Compared to watching short videos, a more effective way for the digital economy to promote rural development is through improving the structure of the rural economy and enhancing the application scenarios of the digital economy. The large-scale transfer of land lays the foundation for the realization of the digital production model and increases the agricultural and non-agricultural income of rural residents. And e-commerce greatly reduces the distance between the production segment and the consumption terminal, activating the potential of the digital village. Therefore, in the future, the construction of rural digitalization should pay more attention to the supporting integration with the industrial development of rural areas, actively promote and cultivate new business forms in rural areas, so that the development of the digital economy in rural areas can truly become an effective way to increase the income of rural residents.

In addition, narrowing the rural income disparity includes reducing the income differences between rural areas within the same province, as well as between different regions, so as to realize the goal of common prosperity. Based on this, each region should optimize the digital village construction strategy according to its own development characteristics. At the same time, inter-regional exchanges should be strengthened. The eastern region has a significant advantage in improving the innovation capacity of rural products and development models, and thus should help stimulate the development of the central and western regions in enhancing digital village construction, thus accelerating digital village construction and realize rural revitalization throughout the country.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China grant number [71673302] and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities grant number [2722021BX018]

Author Contributions

Y.D.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision. C.L.: Data curation, Writing—original draft preparation, Validation. H.S.: Resources, Writing—review and editing.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was financially funded by the National Science Foundation of China (71673302), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2722021BX018).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

1.

Chen Y, Xu B, Zhou W. Urbanization, property income, economic growth and rural income gap-an empirical analysis based on VAR model.

J. Yunnan Univ. Finance Econ. 2017,

33, 74–83.

[Google Scholar]

2.

Wang Y, Li X, Xin L. Has the increase in agricultural labor productivity narrowed the income disparity among rural residents?

J. Nat. Resour. 2018,

33, 372–385.

[Google Scholar]

3.

Wu Z, Zhang X. How much education affects the income disparity of rural residents.

Educ. Dev. Res. 2017,

37, 36–44.

[Google Scholar]

4.

Feng M. Accelerating the pace of China’s rural informatization.

Macroecon. Manag. 2006,

11, 50–52.

[Google Scholar]

5.

Peng C. The logic of promoting digital countryside strategy.

People’s Forum 2019,

33, 72–73.

[Google Scholar]

6.

Zhao C, Xu Z. Mechanisms, problems and strategies of digital village construction in the context of high-quality development.

J. Seek. Knowl. 2021,

48, 44–52.

[Google Scholar]

7.

Wen F. Digital village construction: Importance, practical dilemma and governance path.

Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2022,

4, 147–153.

[Google Scholar]

8.

Liu Y, Lü P. The goals, effectiveness and challenges of digital village construction.

Econ. Manag. 2022,

36, 25–33.

[Google Scholar]

9.

Wang S, Yu N, Fu R. Digital village construction: Mechanism of action, realistic challenges and implementation strategies.

Reform 2021,

4, 45–59.

[Google Scholar]

10.

Wen F. Digital technology-enabled modernization of rural construction: importance, obstacles and development path.

J. Hubei Univ. 2022,

49, 134–141+173.

[Google Scholar]

11.

Li L, Zeng Y, Guo H. Digital village construction: Underlying logic, practical misconceptions and optimization path.

China Rural Econ. 2023,

1, 77–92.

[Google Scholar]

12.

Feng C, Xu H. The practical dilemma and breakthrough path of current digital village construction.

J. Yunnan Norm Univ. 2021,

53, 93–102.

[Google Scholar]

13.

Xie W, Song D, Bi Y. The construction of China’s digital countryside: inner mechanism, articulation mechanism and practical path.

J. Soochow Univ. 2022,

43, 93–103.

[Google Scholar]

14.

Xia X, Chen Z, Zhang H, Zhao M. High-quality development of agriculture: word empowerment and realization path.

China Rural Econ. 2019,

12, 2–15.

[Google Scholar]

15.

Zhu H, Chen H. The level measurement, spatial and temporal evolution and promotion path of digital village development in China.

Agric. Econ. Issues 2023,

3, 21–33.

[Google Scholar]

16.

Jensen R. The digital provides: information (technology), market performance, and welfare in the South Indian fisheries sector.

Q. J. Econ. 2007,

3, 879–924.

[Google Scholar]

17.

Shimamoto D, Yamada H, Gummert M. Mobile phones and market information: Evidence from rural Cambodia.

Food Policy 2015,

57, 135–141.

[Google Scholar]

18.

Wu L. Three points of emphasis for the construction of digital village in the less developed areas in the west.

People’s Forum 2020,

8, 104–105.

[Google Scholar]

19.

Lu J, Chen C. Construction of digital villages in ethnic areas: logical starting point, potential paths and policy recommendations.

J. Southwest Uni. Natl. 2021,

42, 154–159.

[Google Scholar]

20.

Wang Y, Wang H. The effect of digital village on rural residents’ online shopping.

China Circ. Econ. 2021,

35, 9–18.

[Google Scholar]

21.

Hao A, Tan J. The impact of digital village construction on the resilience of China’s food system.

J. South China Agric. Univ. 2022,

21, 10–24.

[Google Scholar]

22.

Li B, Zhou Q, Yue H. An empirical test of the impact of digital village construction on industrial prosperity.

Stat. Decis. Mak. 2022,

38, 5–10.

[Google Scholar]

23.

Chen Z, Zhang X. Can digital village construction alleviate agricultural resource factor mismatch?

J. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2022,

21, 736–743.

[Google Scholar]

24.

Zhang R, Zhong C. Digital village construction and county ecological environment quality—Empirical evidence from comprehensive demonstration policy of e-commerce into rural areas.

Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2023,

45, 54–65.

[Google Scholar]

25.

Shi C. Digital village construction empowers farmers to increase their income: direct impact and spatial spillover.

Hunan Soc. Sci. 2023,

1, 67–76.

[Google Scholar]

26.

Tian W. Measurement of Gini coefficient of provincial residents’ income and its trend analysis.

Econ. Sci. 2012,

188, 48–59.

[Google Scholar]